ARRIVING IN SYDNEY

I sit on Manly Beach and watch three cocky young men play in the shark-infested water. It's cold in Sydney. Winter. But "winter" and "cold" mean fifteen degrees. The city is preparing for the first heat wave with bushfires. The smoke hangs in the air, and I can hardly believe that such a "healthy" city burns so many plants. I feel infinitely far away from Malaysia, and yet, I find aspects that remind me of it wherever I go. They burn garbage in Southeast Asia, not biomass. It's a thousand times worse, but the smoke is there as well. The beach seems clean, and yet large pipes lead into the sea, and signs suggest that in heavy rain the water would be polluted and unsafe for swimming.

GEORGETOWN, NATIONAL IDENTITY AND STREETART

In Malaysia, I relax when I realise that there are women on the streets. I see them with or without the headscarf, with or without the burka, with or without children, accompanied by their husbands or on their own. In its diversity, it reminds me a lot more of Dubai than of Iran. I'm relieved, and at the same time, I realise that this doesn't have to mean anything.

BANGKOK - BOXING AND RELAXATION

Once in Bangkok, I'm fortunate again. I end up in a lovely hostel run by a Frenchman. For breakfast, there is baguette (real baguette made in Bangkok from the only Japanese baker in town), French toast, egg in toast and cereal. The best breakfast I have eaten in a year. I did miss bread! Instead, I get crackling, hissing, crispy baguette. Simple and good. Although there are some negative comments on Booking.com, they refer to the owner, a Frenchman. He has lived in Bangkok for over twenty years but is still an unfriendly, arrogant French man. In reality, he's super sweet and interesting, but French. For someone from the UK or Australia who doesn't know how to pocket the criticism of a Frenchman, impossible. Grumpy French men haven't intimidated me for a long time, so I spend a wonderful time there.

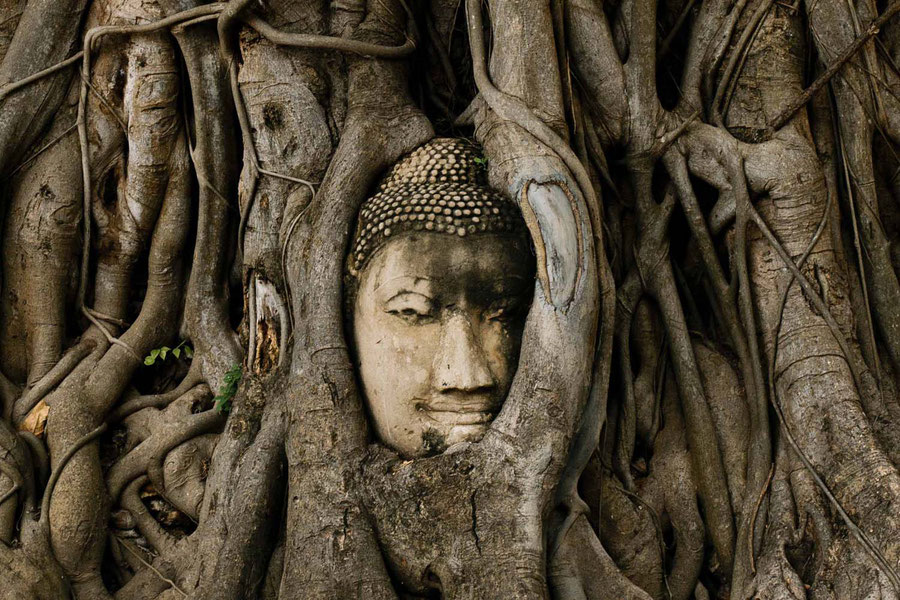

AYUTTHAYA - DOLLS AND TEMPLES

I get on an old bus that brings me to Ayuthaya. I'm kicked out on the side of the highway. My map informs me that it's an hours walk to town, two hours to my hostel. But of course, a number of taxis are available. I don't want to pay the tourist fair, so I take a Vespataxi. However, instead of the official route, the taxi driver drives on the other side of the road. He even rides up the narrow slip road. He transports me to my hostel in, to this date, the worst twenty minutes of my life. The Vespa is much smaller than my last ride of this kind in Kunming (China). I have to keep my twenty-kilo backpack on my back. On the short trip, I pull a shoulder muscle (or something the like), which plagues me for the next four weeks. 100 kilo plus pulling forces are too much for me. And thus I decide to reduce my luggage for the second half of my world trip (but couldn't possibly be expected to do so momentarily). Only after three Thai massages, two mom massages, two Flo massages and four weeks, my shoulder is free of complaints. Lesson learned.

SUKHOTHAI - IN THE BIRDHOUSE

In Sukhothai, the cheapest accommodation is also the most beautiful. There are only single rooms. This little town is not exactly on the main tourist route (but not too far away either). Here you come if you want to see more. All the travel tips I read about this place mention, that one can discover a very similar temple complex with palace ruins in Ayutthaya, just an hour from Bangkok. Both sites are UNESCO World Heritage Sites, so neither is an insider tip. To get here, you have to get off the train and transfer to a bus or travel to Chiang Mai with two different buses (from Bangkok). It's not difficult to get here but won't happen without effort either.

PAI - JUNGLE DREAMS

Pai is widely regarded as a hippie oasis and pearl of the north of Thailand. It's a small village located in a broad valley, surrounded by green mountains. Again, the tourists have life firmly in hand. There is a bookstore selling exclusively English-language titles and many scooter rentals, tour providers and massage facilities. You can leave the main street to get a glimpse of local life. In addition to the ever-present temples, there is a mosque, which breaks up the monotony of the Buddhist life. Here, the men wear Takke and the women headscarves, but otherwise, not much seems to be different.

KUNMING

Kunming is a big city. Not in the eyes of the Chinese, of course. It has only 6.7 million inhabitants, after all. This is common in China. Once more I marvel at the relativity of all things, size in particular. On exiting the train station in Kunming, I get on a scooter taxi, and for the first time, I am on an overloaded bike, like I've seen so many times before. The taxi driver and I, with all my luggage, sit on one little machine. It's getting dark. We slide through traffic. My backpack and I are substantial. We hit the buffer with every major hump. I lean back, so I don't have to touch the driver. It's refreshing to feel the wind blow through my hair and to hold my nose skyward. I hold on with one hand, with the other I check the route my driver is supposed to take. He's a good one, makes no detours and does not talk. Just how I like them.

POKHARA AND THE DOLCE FAR NIENTE

In Pokhara, the second largest city in Nepal, I get lucky and stay in a super comfortable hostel. The dormitories have wooden beds, and curtains surround each, a rarity in Nepal. The city clings to a lake along a road lined by houses and cafes. This place was formerly wetland. The king gave it to the untouchables, as they were the only ones who survived in these circumstances. Today, the city is well on the way to becoming a tourist paradise. The prices of the lakeside estates are rising, and in the heat of the valley, they promise long-awaited refreshment.

BAKTHAPUR: EARTHQUAKE REMINDER

It's late evening when I arrive in Bakhtapur. The sun has already set, and the streetlights illuminate the old cobblestone streets. To get into the old town, I have to pay a hefty entrance fee. Converted its 15USD. That's a lot of money in Nepal. Grumbling, I reach into my pocket. When the inn of my choice is full, I change to a hotel. It's too expensive for me and not good, but what am I supposed to do? I'm relieved to get off the road. Although I feel surprisingly secure in this city, I don't trust that feeling. As soon as I arrive in my four walls, I have a long and rare skype conversation with my big brother. It's cold. I cuddle into bed while I examine the familiar themes that connect us. As usual, my brother disagrees with me and, as always, I fail to verbalise my view of the world adequately. But this is also a piece of the puzzle. A piece that I pick up again and again. I hope that someday practice will make perfect. I have noticed how my ability to communicate increases with travelling.

VARANASI - BETWEEN WONDER AND SHAME

I only come to Varanasi because I get on the wrong train in Delhi. Train journeys in India bring a lot of pitfalls. I get on the train, which is on the right track at the right time, carries the right train number and still drives to the wrong place. I planned to travel from Delhi to Gorakhpur, stay there for one night and then board the bus to the Nepalese border. As my fellow Indian travellers explain, karma has intervened. Fortunately, the train doesn't go in a different direction, just to a more beautiful place. When I get out, I see a white couple, and since I have had no time to get informed about the local hostel situation, I join them.

JAIPUR AND AGRA: ON MY OWN TWO FEET

Arriving in Jaipur begins with fighting for a suitable rickshaw. A critical moment in any arriving tourists experience, as you are being stormed on all sides by drivers who want to earn some money. However, nobody knows where my hostel is (no rarity). I let the rickshaw driver of my choice (crucial detail) take me to the centre and eventually get out of the car after he deliberately drives to the wrong place, does not react to my instructions and finally gets stuck in a traffic jam. Thanks to my Maps.me app, I'm well oriented. I give him the 100 rupees we agreed on at the beginning and walk away in a rage. (It's not smart to not pay them in that situation because they come back to fleece you. Ultimately they are stronger than we are and what are 100 rupees in the grand scheme of things.) Taxi and rickshaw drivers are the worst professions in the world. They are scammers and generally up to no good. It's unproductive to think about it, and yet I do precisely that.

QESHM AND DESERT WELLS

Qeshm is not like Hormuz. It's much bigger. You could almost call it industrial. Almost is the operative word here. Like in Hormuz, women walk around wearing traditional masks as part of their hijab and are dressed as colourful as in India. It's the outward differences that make it possible for me to forget the mainland.

HORMUZ ISLAND

The wind is blowing in our faces. Hormuz harbour is brimming with life. Once again, J. has made friends with a young Iranian who has so little interest in me that I find myself judging him following Iranian standards. More than thirty, not married, interested in the handsome, blonde J., who, to make matters worse, also wears an earring. For Iranians that is proof of his sexual orientation. A circumstance that at first makes me smile, but when he spontaneously decides to come with us, I start thinking. Will this be another unspoken promise that will never be fulfilled? They keep adding up. Together we take one of the converted Vespas to the most beautiful corner of the island. That he pays, because we would prefer to walk, but he says, it's too long. Despite all my misgivings and doubts about J.'s way of travelling, I can't help but appreciate how quickly he brings us to where we dream of going. Of course, everything is unpredictable, luck and coincidence, but there are a few moments when I have to pinch my arm in disbelief.

ALAMUT - TWOGETHER

From the desert, I had to return to Tehran to meet up with J., my travel partner for Pakistan. We had to apply for the appropriate visa. We both didn't like the capital for different reasons, so we decided to hitchhike to Alamut Valley, breathe mountain air and try if we loved travelling together or not.

YAZD AND THE DESERT

In Yazd, I was pretty exhausted, and my nerves lay bare. If I could have beamed myself out of Iran, I would have done it then and there. But since I still had the hope of travelling to India through Pakistan at the time, I clenched my teeth and ventured on. I planned to write and somehow forget that last night in Tehran.

KASHAN

In some aspects, Kashan is one of the most beautiful places I visited in Iran. It's conservative. The streets are filled with women dressed in black and men who think it's alright to harass western women. They teach their sons that it's normal to chase them through narrow streets and throw stones at me. I manage to escape to the safety of a hostel. Fortunately, I meet other travellers there. In Kashan, the tourism industry isn't as present as in other cities in Iran. A lot of times it feels as if I'm discovering this place on my terms. Some moments are wonderful. I'm fortunate to explore old and empty historic houses. Some are furnished, but the most beautiful are empty. The exquisite frescoes and murals give the familiar forms a unique look. I could live in a house like this. It would have to be empty, Steve Jobs style. Furniture always seems just a little bit too much, too pompous.

TEHRAN

In Tehran, I spend far too much time. I return again and again because of the India and Pakistan visas. In the end everything for almost nothing. I get the India visa after an artificially complicated process. Visa procedures here resemble organised crime. Information is trump. In the end, I have a 180-day visa with a single entry. For the same price, I could have had a six-month visa with an infinite number of entries. It always happens when I stumble into stuff like that exhausted. It annoys me, but I can't change it, so I move on.

MASULEH

R. takes me to the mountains. At seven in the morning, we get into her father-in-law's car and rush off, both drowsy. The evening before we ate and talked late into the night. After four hours of sleep, R. dozes of within a short time. For me everything is new. There is no way I can sleep now although I can hardly keep my eyes open. I toss around for some time and eventually rest my eyes on the retail stores lined up along the street. Auto mechanics, screw shops, auto door repair shops, bakers, electronics retailers, fruit stands and much more. They line up along the road from village to village. The mountains still seem to be far away. How long will we be travelling? I don't know. I forgot to ask.

RASHT

Sometimes friends meet cool people on their trips abroad. That's what happened to J. (one of my former roommates) and R. (my hostess). Rasht is not on the classic tourist route and I probably wouldn't have gone there, hadn't there been R. and M. It's a lovely place that is not overtly beautiful like the big touristic magnets in Iran. It has a charming bazaar and countless mosques but other than being in a stunning region, there is not much there.

TABRIZ

In Tabriz, I am allowed to look over the shoulder of S. and H. With amazement I see how dominant women here are behind closed doors, how much appreciation they are shown by the men in their lives. My first encounters here show me that everything I thought I knew about this country is not accurate. The spectrum is bigger, it's not peace, joy and pancakes, but it's only hell on earth when you marry the wrong or no man. The girls spend a lot of time locked up in the family living room and watch Turkish tv series, cook or discuss the here and now. The living room is the linchpin of life. Being in the middle of it all is lovely. The familiar feeling of a big family unfolding in front of my eyes is very much welcome.

JEREVAN

From now on out, I move through Yerevan with my big headphones. Most of the time I listen to loud music that drowns the omnipresent honking of the cars. This filters out an incredibly stressful aspect of walking on the streets. I learn to move safely, and with purpose. I jump from Mashrutka to Mashrutka, drive to the wrong places and turn around again. I follow my inner compass. I don't know the way and live with the resulting detours. I learn to move through the cars, learn where to look and what to pay attention to until I can deal with the noise without music on my ears.

JERMUK

Within a few hours of moving across the Georgian border, I fell head over heels in love with the country. However, after about three weeks, this enthusiasm had already relativised itself a bit. I was sure Armenia would have a hard time living up to its neighbour's awesomeness. In fact, my interest in Armenia has grown slowly but steadily over my stay. Armenia is not easy for me to enjoy. I had a lot of negative experiences but always counterbalanced by mostly small but positive moments. Especially Yerevan has a place in my heart. I know that I would find the province quite enchanting if only I weren't alone.

SEVAN LAKE

On Lake Sevan, I stay for exactly four hours. Then, I decide against my original plan and move on to Yerevan. Initially, I wanted to camp in the wild for two days, enjoy the spectacular sunrise and sunset, take time and breathe. Like I did in Georgia. I needed a break again. In Armenia I read, this should work without problems. But I can't shake the feeling of being watched. I don't feel safe. The constant honking of strange men in their cars, reminds me, that they are watching. On the one hand, they want to "help" me, and the scenario would be very different, had I not been alone. Men and couples can enjoy this kind of attention and file it under "hospitality" or "help". For single women, this quickly turns into harassment. Every contact begins hospitable, that's just how things work here. But too often, these exchanges end in unpleasant discussions and insults.

DILIJAN

My visit to Dilijan is marked by the breach of trust described in the previous post. I felt like I was done with Armenia. Dilijan is a nice little town, but the position of women became more and more apparent to me. Through R., whom I met in Alaverdi, I got the contacts of I. and S., also volunteers. Both come from Germany and have been contesting the Armenian waters for several months. They learn the language, can already read and have experienced some exciting moments. Since they were sent by the European Volunteer Service, they have an Armenian guardian. This is blessing and curse at the same time. A curse because every movement is observed and commented, and a blessing because it's indispensable. This constant observation is typical for this country. Here, everyone knows (or believes to know) about everyone's business.

ALAVERDI, SANAHIN, HAGHPAT

In Georgia, I take a Mashrutka headed to Yerevan, and three hours later I am in Alaverdi. Alaverdi is a small town in northern Armenia. As soon as I step off the bus, I notice a different wind blowing. Everyone looks at me, and in a short time, four of the ten or so taxi drivers had asked me where I wanted to go. I rebuff their offers, exchange money, buy fruit, and go to a cell phone store. There I meet one (of four) Armenian women in this city that speak perfect German. She provides me with the right sim card and gives me a sense of security. Back on the main square, the taxi drivers rush to my aid, again. For them, it's monstrous that I want to take a bus, not a taxi. After all, I am a European, and therefore it's my duty to spend as much money as possible here. In the beginning, I had refused the offerings with a friendly smile, but now I put on a determined look and stare angrily into their faces. In the end, I just ignore them. I don't care to be polite anymore.

A NEW BEGINNING

Georgia. The Caucasus begins here from one second to the next. At the place where my Russian taxi driver drops me off, the valley is broad, and the mountains look like adolescent boys. The border crossing to Georgia is one kilometre south in the notch of a mighty canyon. The three thousand meter high peaks rise in self-confidence on all sides and command awe. Instead of the military, the border is guarded by a monastery. There, I take my first break and congratulate myself on crossing the border. I have started to celebrate the small stages because sometimes the stretch in my head is so much wider than the kilometres, I physically travelled.

BALAKLAVA

Balaklava is a small seaside town, former military base and tourist paradise. Old gentlemen sit with hats in the harbour, hold their fishing rods into the turquoise water and call out to each other from time to time. The people here are beautiful, like the landscape they are masterpieces of time. In the harbour are yachts from America, Europe and Russia. As usual, the rich of this earth know exactly where it's worth living. The coast is mountainous and rugged. The land in this part of Crimea falls in cliffs into the blue sea. Yellow dry grass dances with cornflowers in the evening sun and the crickets sing their evening song.

ESCAPING

After three weeks, I finally get a two-day break. Two of my colleagues bring the children back to Moscow, two more stay in the camp with me. Apart from us, two girls remain for the second round. Since they mostly long for sleep and good food, I sneak out on my own. At half past seven in the morning, I'm standing at the bus stop. I want to see more of this place.

SOVIET SUMMER CAMP

Here in camp, time has stopped. The wooden benches are painted in the colours they were painted in during Soviet times. The same people perform the never changing summer jobs. Most of them are tanned seniors, whose skin is leather like. I presume that they are locals, but since I haven't seen much more than the camp on this peninsula, I don't know. Like the Russians, they seem unfriendly and insist on the most abstruse regulations, but then, maybe they adapted? Some of these rules make me cringe and sometimes almost laugh out loud. For example, only ten children are allowed in the sea at the same time and ideally, after 10 minutes, they are called out. Drinking water is not important, and children are supposed to move in pairs. Always. The only way I survive this is by silently not enforcing all of the rules. It's a process, an ongoing negotiation.

This camp isn't fancy. Money is saved in all areas. Food is watered down and consists of overcooked pasta with sausage, buckwheat or rice with meat and a little bit of flabby sauce. Sometimes there is a plate of soup, and we win the jackpot when there are stuffed piroshki (Russian pastries, at times filled with jam).

SAINT PETERSBURG

The third day I dedicated to exploring the city. It was still depressingly cold. -25°C, I had trouble keeping my limbs alive. My nasal wings felt as if covered with a thin layer of ice. A weird feeling. In the shop windows, I regularly checked that no icicles grew out of my nose. My cheeks, nose, and hands were bright red from the cold, and during the day I began to debate with myself whether to call it a day and crawl into bed. I resisted this paradise-like alternative and ventured on. After all, the idea of visiting this city in winter was something I embraced full-heartedly, hypothetically.

TAMPERE

I only visited Tampere because so many people told me that I couldn't miss it. My touristic curiosity had already been exhausted in other places, and I didn't expect to discover too many unknown aspects of Finnish life. I felt that I had seen most of it before, and I was more interested in the landscape of the north than in a large(ish) city in the south-west of Finland. However, as I had learned to believe my Finns when they recommended something, I drove to the city that is also called the Manchester of Finland.

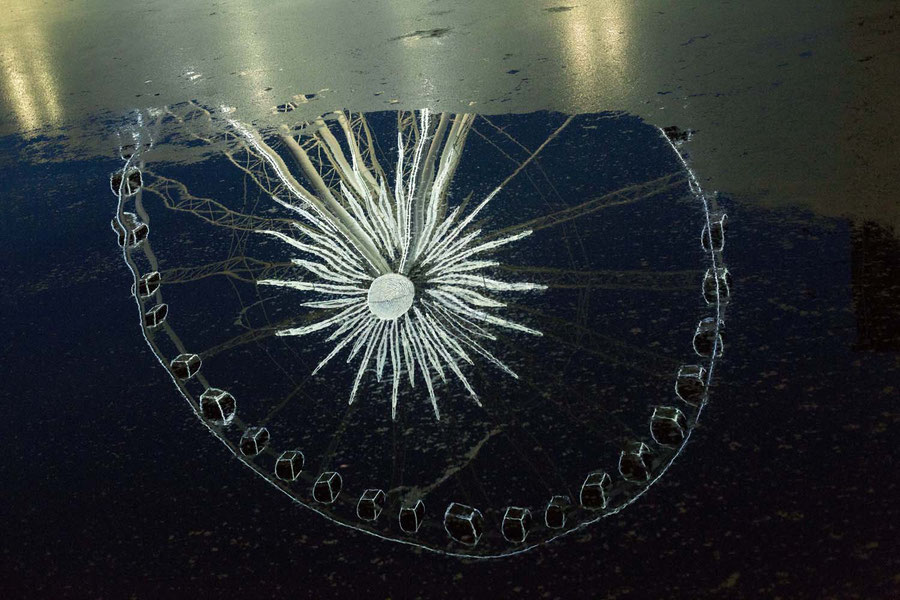

PORVOO

Porvoo sits on the southern coast of Finland, one hour east of Helsinki. With fifty thousand inhabitants it's one of the twenty most populated cities in Finland. It's particularly attractive because it has a relatively large area of old wooden houses, an old town with a town hall and a cathedral. After Turku, it's the second oldest city in Finland. Through it flows the river Porvoonjoki, which, when I was there, was charmingly frozen and sang under the ice. Wale like sounds echoed across the river like an electronically distorted didgeridoo with a long echo.

ROVANIEMI

In my last weeks in Germany, a good friend had directed my attention to the independent film scene in Rovaniemi. It's a town in northern Finland, on the southern edge of Finnish Lapland, at the polar circle. Here the sun sets early and rises late during winter. Also, it's damn cold. I visited a KinoKabaret there. It's a festival that is more like a workshop, where we shoot short films. A Kino cell is a group of short film enthusiasts, who meet a few times a year to realise projects in a short period. If there is a meeting somewhere, there is a shoutout on the Internet and whoever wants to come, can come. They are held all over the world. Whenever I can, I attend such meetings. You meet interesting people and get to look at a city on a whole other level. If you want to know more, read this, this, or that.

HELSINKI

I travelled from Turku to Helsinki by train. On it, I noticed playgrounds for children. In front of each staircase leading to the lower part of the waggon was a gate to secure the children's safety. The small area in the compartment consisted of a small slide and some games. In the train I travelled with was one such compartment in each car, not like in Germany, where one, if fortunate, has access to a small glass box for three adults and two children on a train for 750 people. With each ticket came a place reservation. Therefore the train felt almost empty, as everyone sat comfortably in their seat. I liked this orderly calmness. The Finns seemed to be a people after my own heart. No one sat down next to me or tried to start a conversation. The conductor kindly told me that I was in the wrong seat: correct seat number, wrong car. It seemed important to him, so I took my belongings and waddled into the next car. As long as you follow the rules, Finland is great.

TURKU

Finland. I was there. This is where I would have to organise an alternative, finally create new facts. It was the last country before I would leave the perceived security of Europe and for the time being my cultural habitat. I realised that this border crossing was one of the biggest hurdles. I have experienced not speaking a common language with the people around me before. That didn't worry me as much as my ignorance about the unknown rules and conventions. I swayed between fear of the foreign, the sheer size of Russia, entering the dominion of Putin, and the certainty sleeping somewhere in my head that beyond the borders of Europe people had the same basic needs. I now faced the tasks I had shrugged off before because I had to get to Finland first.

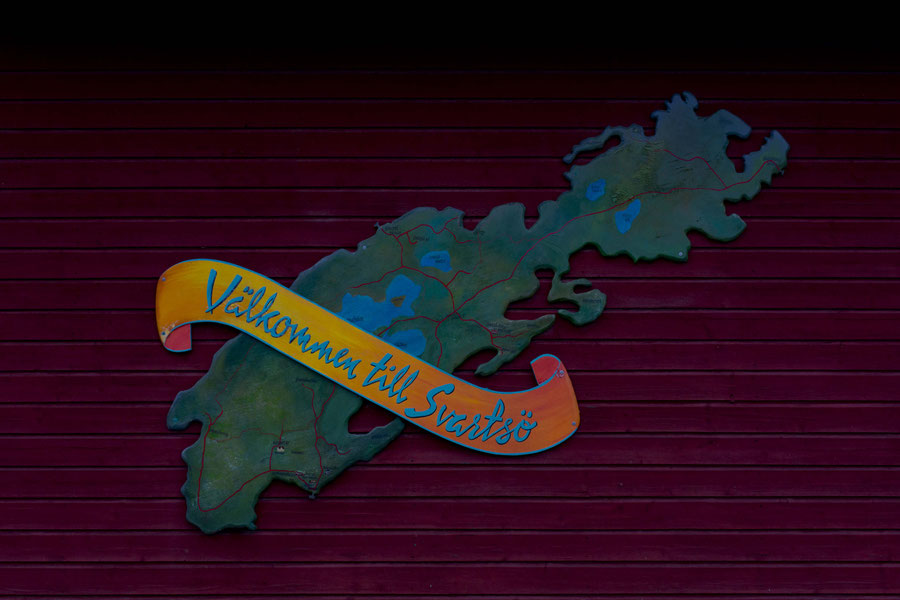

THE ARCHIPELAGO: SVARTSÖ

The best part of my stay in Sweden was the visit of the Archipelago. Islands have a special place in my heart. Here I saw for the first time nature, which should become so familiar in the coming months. The north with its granite floors, the wooden sheds, the moss and the numerous and partly absurdly large boulders. Getting to the islands was not easy. R. and I needed two attempts, but in the end, we made it. The crossing was wet, the day was wet, and in the end I was wet. Wet, cold and satisfied. Who would have thought?

STOCKHOLM

R. and I had booked a cute little AirBnB, which was a little out of the way in a beautiful area in Stockholm. Nacka Strand. We wanted a comfortable place to cook, sleep and get organised. We slept in a converted shed, in front of an old Swedish house. The red kind you see all over Scandinavia. The decor in the shed was masculine, it was dry and warm, the beds were comfortable and the kitchen functional. Our hosts were friendly and helpful. AirBnB proved itself once more. Stockholm greeted us with a grey wall of clouds and the first three of the four days it was raining non-stop. Only on the last day we got to see the sun at all, which gave us a small taste of Stockholm in the summer. Enchanting.

TALLINN

Back to Estonia...

In Tallinn, I didn't know what to do with myself. The city and the people were lovely, and my AirBnB was great, although I originally planned to couch surf. I presumed that a little company would give my stay a little sparkle. The people I had written to were all busy doing other things; I decided to explore the city on my own. I was a bit relieved. I was beginning to realise that another random connection would not necessarily solve my problem. However, I also knew that my hands were tied, for now. I wouldn't be able to make plans or decisions concerning my travelling. I was supposed to meet my friend in Stockholm that weekend and therefore could make any significant changes (like finding somewhere to stay long term) only when I arrived in Finland. I couldn't start problem-solving just yet. I knew I wanted to do an AuPair in Russia but didn't know how to organise a visa or a family. Although I knew the relevant Internet pages, the offers from Russia were rare. Also, I was not at all sure that the AuPair would solve my problems. I found myself unable to change anything and began to explore the city.

KURESSARE

This island is an incredibly beautiful place. There was everything I needed to live and much more. My hosts took good care of me and provided all the tips I might have needed. The end of autumn was already noticeable. The light had a winter quality and the nights were freezing. The rhythm of life, dictated by the fire, did not lose its appeal for the whole week.

PANGA PANGA

I walked to the nearest town: 6.9 kilometres. I would never have done this voluntarily four weeks ago. It took me only an hour, in Poland it had been three more for the same distance. Well, an hour was still 6 minutes more than I had calculated and so I came too late for my bus. Here on the island came the buses on time or too early, I was told. I ran only pro forma to the bus stop but behold. There he was. The bus to Panga. I went in; the bus driver spoke good English (after Poland and Lithuania I am surprised when older folks speak it at all) and even a few chunks of German. He was happy to see me and chuckled at the idea of me wanting to go to the cliff on my own, which was probably a rarity. When I arrived, I understood why...

SIGULDA & KRIMULDA

Sigulda is a small town from which you can easily explore the Gaujatal, one of the national parks in Latvia. I lived in an AirBnB, which will soon become a hostel. The owners were eagerly renovating the house during my stay. My room was huge and accommodated two double beds. Since I was there on the weekend, I had the joy to share this busy spot with the local weekenders only. The trees stood in their autumn colours, and the Gaujatal was at its best. There were gondolas, hiking trails, beautiful old wooden houses, historic summer residences and even an adventure park. With a bit of time, you could experience it all, if you were into that sort of thing. (The only “active” holiday I enjoy is skiing.) I kept to the small cafes and bakeries, where I got sweet and salty pastries for 50 cents (which tasted excellent) and made my way into the forest. There were old trees, beautiful ruins and mushrooms, mushrooms, mushrooms. Of course, there was an abundance of castles (which I foolishly ignored).

GDYNIA

When traveling, there are places that one would not visit without the guidance of a local. Gdynia is such a place. It was part of Trójmiasto (Polish for tricity), consisting of Gdansk, Gdynia, and Stopol. It was a beautiful coast, with a beautiful beach like straight out of a picture book. Here was once the summer center of the region, or at least it looked like it was. The sun set behind the trees and as a result, the red light of the sun was lost in the blue sky. Since there were no clouds, or only a few, the dramatic effect of the setting fireball was lost on the horizon. It could have been spectacular and it felt as if all the ingredients for a magical show had come together, but unexpectedly dissolved into thin air on the spot.

GDANSK

In Swinouscjie, I got on the train to Gdansk and drove along the coast of Poland. I knew I missed a lot by letting the whole country pass by like this. However, I felt that I would be able to travel to Poland at any time, even if I was older, had children, or was otherwise restricted. This conviction was a little strange and unfounded, as this was the first time I visited our neighboring country but still... It was beautiful and full of forests. The train was incredibly cheap, fast and comfortable. The railway stations were either made of ready-made concrete, built during the Soviet era, like they can also be found in East Germany, or carved from wood, like before the world wars. They were made to look old. You got a feeling for how grand it must have been then, when women in furry coats, corsages and grand hats waited for steaming trains to take them away...

ŚWINOUJŚCIE

For the first time on this journey, right at the beginning, I realized that things are planned and then executed. I had a dream, I planned it and now I am living it. This was such a banal realisation but it hit me hard. I wanted to break into a big laugh when arriving on the beach in Ahlbeck. The euphoria rose in me as I slowly saw the sea appearing behind the dunes. The white sand on the beach and the children in yellow raincoats flying their kites looked like out of a picture book. A never-ending stream of German seniors walked along the surf while the seagulls were screaming. The sand was divinely white and warm.

HELGOLAND

For three days I went to Helgoland with my grandma. Her father grew up on the island, and together with her children, she continued to visit her aunt during summers. My mother does not seem to have been impressed by the island at the time. As far as I can remember, she was always keener to go to France. The German coast, whether the Baltic Sea or the North Sea, bored her and therefor was presented to us kids as being dull. As a result, I was almost 28 years old when I first laid eyes on what remained of my great-grandfather's home. After our little trip, my grandma showed me the old photos and engravings from and of the island. Especially some that show the island before the second world war. It must have been a very nice place. These are particularly exciting when you know the island today. They showed my grandma as a toddler on the then beautiful old pier, my great-grandfather as a tall blond man exercising on the dune, pictures of her parents in the process of being “ausgebootet” on a Börte (a very strange process in which the passengers of large ships are thrown (!) into smaller seaworthy fishing boats), pictures of the family-owned hotel, whose remaining silver spoons used to cut the corners of my mouth when I was a child, and other small details of a life completely alien to me. (The love poems and bon mots of my great-grandfather addressed to my great-grandmother, many of them quite racy, were especially wonderful.) This explained the Nordic half of my grandmother's heart, as well as her fondness for literature and poems. (There was not much else to do on the island during winter and it is rumoured that my great-great-grandfather may have been affiliated with the local lending library...).